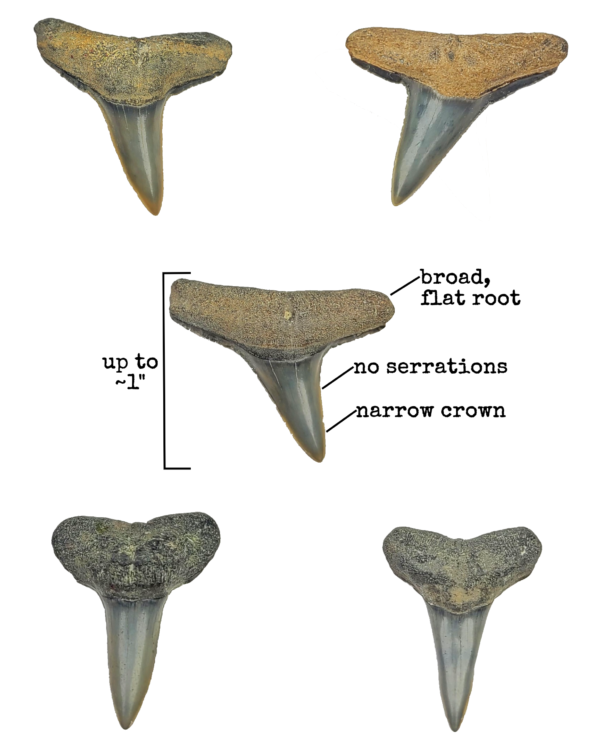

Lemon Shark (Negaprion brevirostris)

Modern lemon sharks primarily inhabit shallow, coastal waters of the eastern hemisphere. They’re thought to have evolved during the late Cretaceous period, some 75-95 mya (million years ago), meaning they co-existed with dinosaurs. Though relatively large (growing up to 11’ and 300+ lbs), they are a docile species and pose very little threat to humans. They’re named after the yellow hue of their skin, which offers excellent camouflage in their preferred shallow, sandy hunting grounds. Their teeth lack serrations, have narrow crowns with broad, flat roots, and resemble the letter “T”.

SHARK FACT

Sharks evolved into their modern forms during the Jurassic period some 200 mya, though the direct lineage of shark-like fishes (which some scientists lump into the broader “shark” family) goes back to at least the Silurian period, 440+ mya. Here’s a list of things “sharks” are older than: trees; amphibians; dinosaurs; reptiles; birds; Pangea; the Atlantic Ocean; the Rockies, Alps, Himalayas, and Andes; Saturn’s rings; and Polaris (the star itself, not just its run as the “North Star,” which is a super interesting astronomy tangent – Google “north star precession” to learn more!).

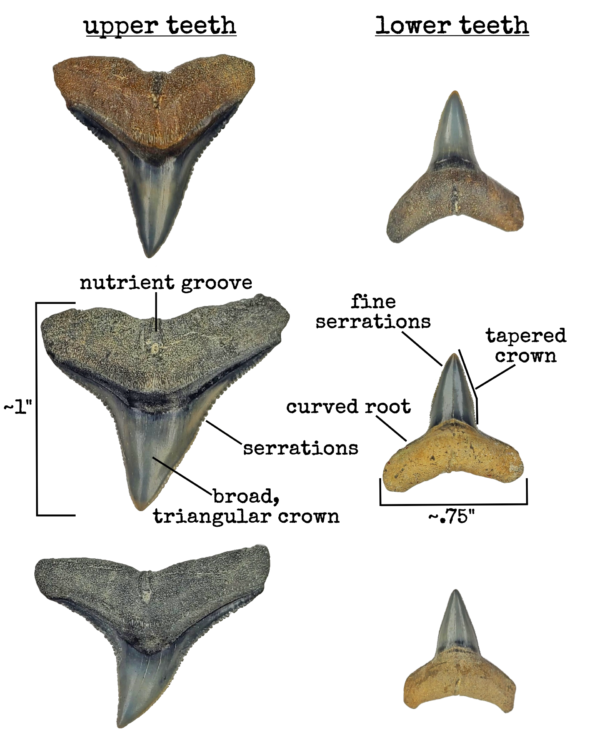

Bull Shark (Carcharhinus sp.)

Bull sharks are one of many species in the broad genus Carcharhinus, which also includes the dusky and silky. Teeth from within this genus often look very similar, making them difficult to tell apart. As such, they’re typically grouped together by collectors and simply referred to as “bulls.” Highly freshwater tolerant, bull sharks have been found in rivers over 1,000 miles upstream. Aggressive and unpredictable, they account for multiple attacks on humans every year, though luckily most aren’t fatal. Their upper teeth are broad and triangular with well-defined, tapering serrations (coarser near the root and finer at the tip), a plunging root, and a prominent nutrient groove while lowers, which are often confused with lemon shark teeth, are narrower, smaller, very finely serrated, taper inward about halfway down the crown, and have a curved root.

SHARK FACT

While the teeth of most other animals are firmly rooted directly into the jaw, shark teeth are held in place by special connective tissue in the “gums” and are lost continuously throughout a shark’s life. Most sharks have around 50 tooth positions, with 5-15 rows of teeth growing in each one. These rows operate like a conveyor belt: as one tooth is lost or damaged, a new one moves forward to take its place. Some sharks can go through 35,000 or more teeth in a lifetime. That’s part of the reason you find so many of them while fossil hunting!

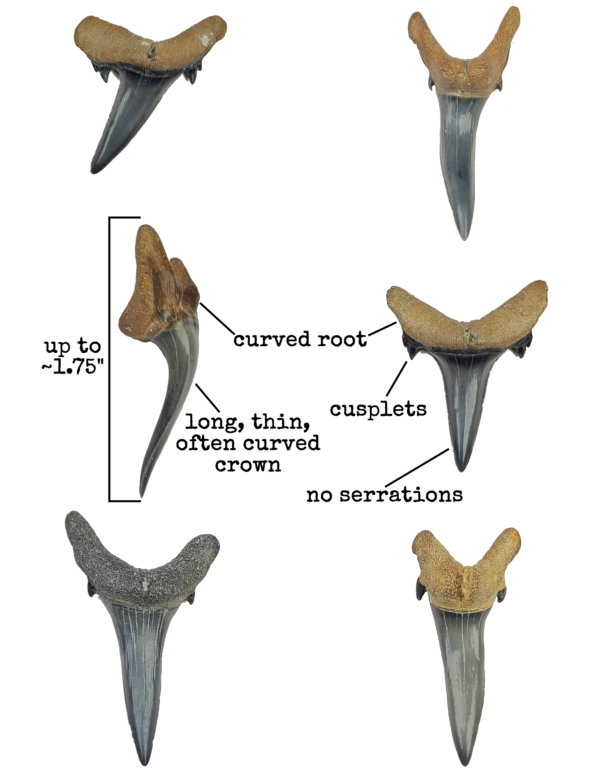

Sand Tiger Shark (Carcharias taurus)

Sand tiger sharks have been around for tens of millions of years. They inhabit temperate and sub-tropical coastal waters worldwide, with adults growing up to 11’ long and 350 lbs. Despite their fearsome appearance, they pose minimal threat to humans, instead using these long, needle-like teeth to grip their desired prey: slippery fish, smaller sharks, rays, and squid. Interestingly, they’re the only sharks known to “gulp” air at the surface. They store this air in their stomachs in order to achieve neutral buoyancy, which allows them to hover motionlessly just above the seafloor in wait of prey. A collectors’ favorite, sand tiger teeth are long and needle-like with tiny cusplets on either side of a markedly curved root.

Shark Fact

You may have heard that if a shark stops moving it will no longer be able to breathe and eventually die. But is this actually true? For some sharks, like the great white and whale – yes! As obligate ram ventilators, the moment they stop moving, oxygen-rich water stops flowing through their gills. But many sharks, like the sand tiger, have special adaptations to combat this problem, such as buccal pumping, in which muscles in the cheeks are used to draw water in through the mouth and back out through the gills, ensuring a constant supply of oxygen-rich water to their motionless host.

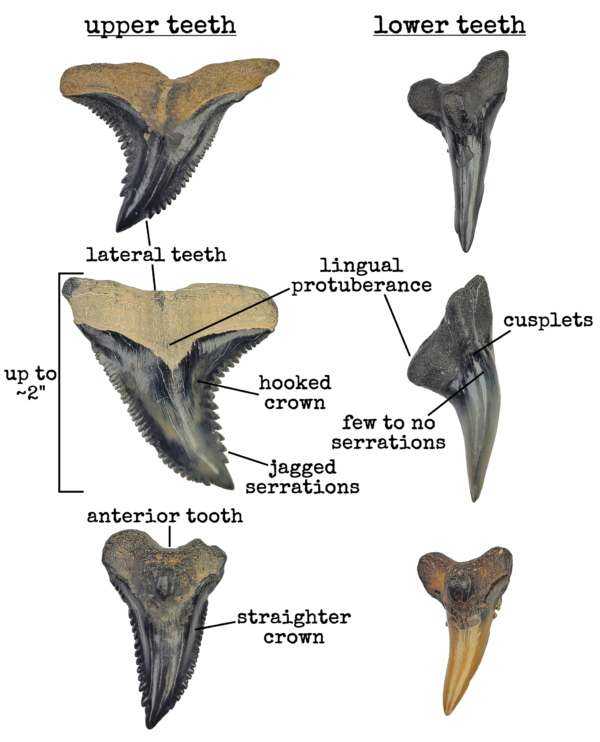

Hemipristis Shark (Hemipristis serra)

Hemipristis serra, aka the snaggletooth shark, is an extinct weasel shark that was widespread during the Miocene (~23 to ~5.3 mya, or million years ago). It was significantly larger than its 8’ long extant (still in existence) cousin, clocking in at 20’ in length. Upper and lower hemi teeth look quite different (and until recently were believed to be from two completely different species) and had opposing functions, with the broad, heavily serrated uppers acting as knives, cutting and tearing flesh, while the pointy, lightly or un-serrated lowers acted as forks, spearing prey and holding it in place. Note that upper lateral teeth (those toward the sides of the jaw) have a significant curve while upper anterior teeth (those toward the center of the jaw) are straighter and narrower. Lowers, which are often confused with sand tiger teeth, can be distinguished by the significant lingual protuberance, or hump, in the center of the root.

Shark Fact

When an animal has upper and lower teeth that differ in size and shape it is said to have dignathic heterodonty (die-NATH-ick HET-err-oh-don-tee). Many sharks exhibit this trait (including several others listed here, such as bulls), but few as markedly as the Hemipristis.

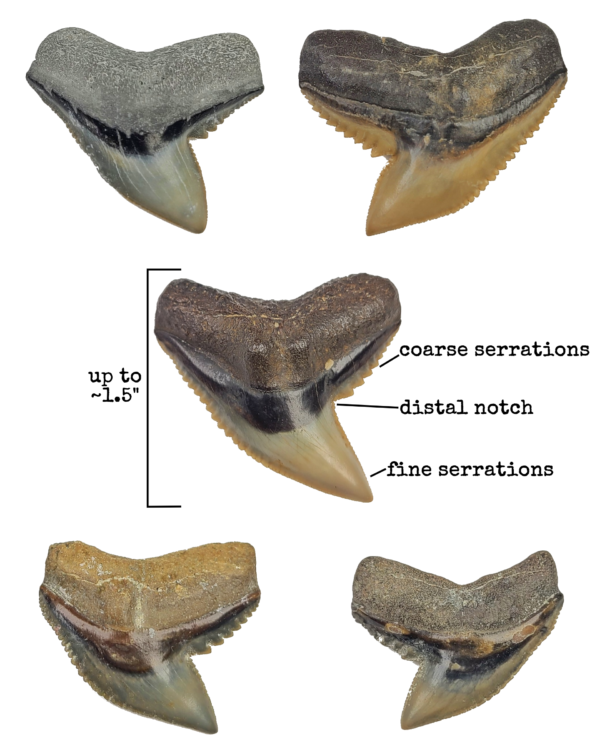

Tiger Shark (Galeocerdo cuvier)

Tiger sharks derive their name from the spots and stripes that dot their backsides, though these typically fade with age. Legendary for their diverse diets, common prey includes fish, birds, seals, dolphins, whales, crustaceans, squid, sea snakes, other sharks, and, notably, sea turtles. Edible items aren’t the only ones on the menu, however, as they’ve been found with everything from license plates to fur coats in their stomachs. Though their large size and dietary ambivalence make them dangerous to humans, attacks are still rare and fatalities even more-so. Among the most iconic shark teeth, they’re easily identified by their unique shape: a broad, plunging root and telltale notched, complexly serrated crown (their serrations have serrations of their own!)

Shark Fact

The size and shape of each species’ teeth can tell you about their diet: long, needle-like teeth are ideal for gripping slippery fish and squid; large, triangular, serrated teeth for slicing through larger fish and especially marine mammals; and broad, flat teeth for crushing shelled and armored prey. Then there are non-functional vestigial teeth, as in the case of filter-feeders like basking, megamouth, and whale sharks, which are merely evolutionary remnants from earlier ancestors and no longer serve any practical use.

Megalodon fragments (Otodus megalodon)

The megalodon is the largest shark of all time. It terrorized seas worldwide from ~20 to ~3.6 million years ago, growing to an estimated 60+’ long and weighing 60+ tons. Its jaws maxed out at nearly 10’ wide and came equipped with up to 276 teeth (46 tooth positions with six sets growing in each row, or file) that could grow to over 7” long, with the largest tooth on record measuring 7.48” from tip to corner (which is how shark teeth are typically measured). Possessing the strongest bite force of any animal in history at an estimated 40,000 lbs/sq inch, it feasted on large marine mammals such as dugongs, manatees, sea lions, seals, dolphins, and even whales, in addition to sea turtles, large fish, and other sharks.

It’s thought to have primarily hunted in warm, shallow seas across the globe, as evidenced by its fossilized teeth being found from Australia to Indonesia, Morocco, Peru, the entire southeastern coast of the US (from Florida to Maryland) and beyond (indeed, its teeth have been found on every continent except Antarctica). While scientists once believed that the megalodon was an ancestor of modern great whites, we now know that they evolved from completely different lineages and are not closely related at all.

Megalodon teeth are differentiated from other species by their sheer size and the fact that they possess serrations and a bourlette (a triangular or V-shaped band between the root and crown) while lacking cusps, with uppers being broad and triangular, lowers being somewhat narrower with more sharply angled roots, and posteriors having short, squat crowns with wide, thick roots.

Shark Fact

The side most people think of as the “front” of a shark tooth is actually the back side! The labial, or outward facing side of shark teeth is actually relatively flat and featureless, whereas the lingual, or inward facing side is the one that gets all the attention (as evidenced by every tooth in this ID guide being featured from the lingual side

Alligator teeth

Mature alligators have 80 conical teeth, which they lose and replace by the thousands over the course of their lifetimes. Replacements grow in from below the existing tooth at about the same rate as human fingernails. A rootless, hollow-bottomed tooth was lost by a living animal, whereas a rooted tooth came from a deceased one. The largest (modern) American alligator on record was captured in 2014 and was nearly 16’ and weighed over 1000 lbs. While this seems (and is!) enormous, it paled in comparison to its Miocene contemporary, the marine (saltwater dwelling) American crocodile, which is thought to have reached 30’ long and over 8,000 lbs.

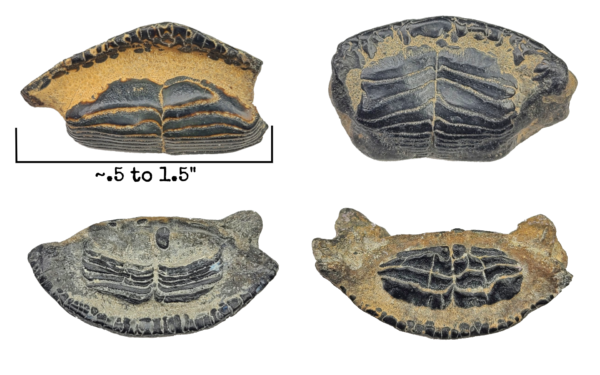

Burrfish mouth plates

Burr, puffer, and porcupinefish belong to the broader “blowfish” family (taxonomically, order). Many of the fish in this order possess sharp, spiny armor (hence the names “burr” and “porcupine”), some are highly venomous, and all have the ability to inflate when threatened by predators. Burr (featured here) and porcupinefish (which look similar but are typically larger, with up to 20+ layers of stacked enamel) have fused teeth, while pufferfish teeth are unfused (and significantly more rare). These “mouth plates” form a beak of sorts and are used to crush the fish’s armored prey. On the menu? Crabs, clams, sea snails, shrimp, urchins, barnacles, and more.

Misc tooth/enamel fragments

Not every tooth you find is complete. In fact, the vast majority of specimens are broken! Common tooth fragments include horse (pictured here at the top), mammoth, mastodon, deer, tapir (bottom left), llama, camel, peccary, beaver, capybara (bottom right), bison, ground sloth, alligator, giant armadillo, glyptodont, raccoon, rodent, and others. From browsers to grazers, carnivores to herbivores, and everything in between.

Stingray barbs

There are around 220 known living species of stingrays worldwide, with countless extinct ones. Closely related to sharks, they’ve been around since at least the Jurassic period (~150 million years), meaning they co-existed with dinosaurs. Their venomous, serrated tail barbs are only used as a last line of defense, as rays would rather flee than fight. When deployed, they’re whipped to the side or over the stingray’s head like a scorpion.

Stingray teeth (aka mouth plates)

Stingray teeth grow in rows, fusing together to form broad crushing plates on the tops and bottoms of their mouths which they use to squash the shells of their armored prey. These plates typically break apart into individual teeth after rays die, but on rare occasions can be found still fused together.

Turtle/Tortoise shell

A turtle’s shell comprises the upper shell, or carapace (KARE-uh-pis) and the bottom shell, or plastron (PLA-strun). Though these shell fragments are some of the most common fossil finds in the state, their often mesmerizing patterns make them a favorite with collectors.