Sharks, along with their close cousins rays, skates, and sawfish (and distant cousins chimeras) comprise a class of fish called Chondrichthyes (kahn-DRIK-thee-eez): those with cartilaginous (car-tuh-LADGE-in-iss) skeletons rather than ones made of bone. Their earliest direct ancestors (which took on all kinds of bizarre forms we’d hardly recognize as sharks today) date back to at least the Silurian period, ~440 mya (million years ago), with what we’d consider to be “modern” sharks having evolved during the Jurassic period, some ~200 mya.

Shark teeth are embedded in the “gums” rather than the jaw, and are constantly lost and replaced throughout a shark’s life. Some sharks can go through as many as 35,000 teeth in a lifetime. The size and shape of each species’ teeth can tell you about their diet: long, needle-like teeth are ideal for spearing slippery fish and squid; large, triangular, serrated teeth for slicing through larger fish and marine mammals; and broad, flat teeth for crushing crustaceans and mollusks.

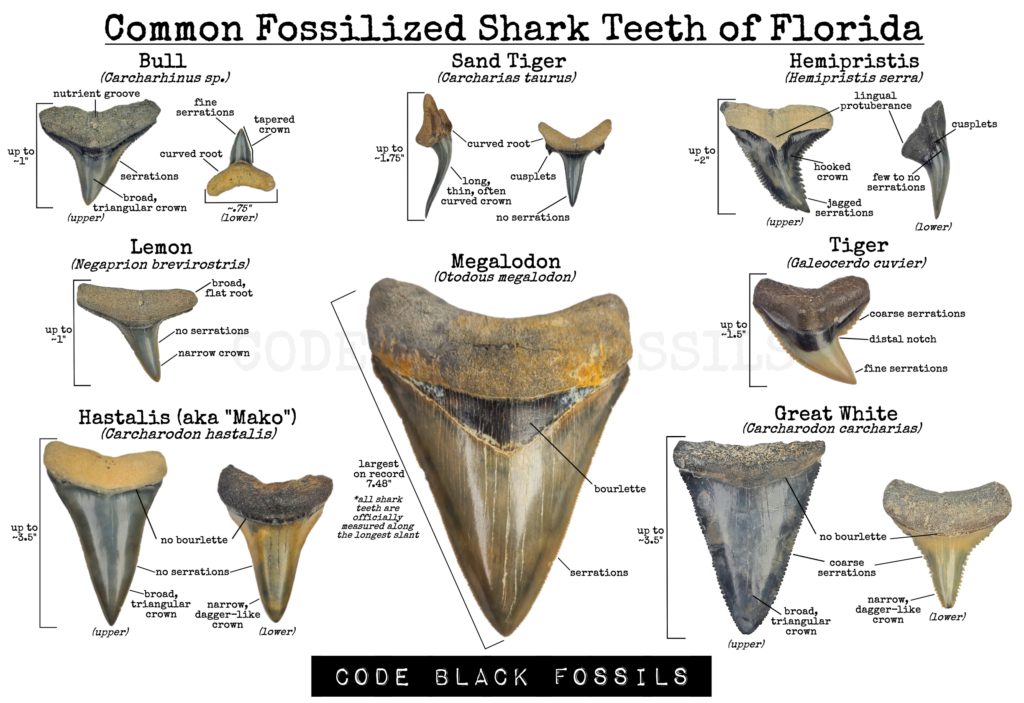

You can find numerous species of fossilized shark teeth in Florida, including (but not limited to!) – in roughly increasing order of rarity – lemon; bull/dusky/other closely related species; sand tiger; hammerhead; hemipristis (aka snaggletooth); tiger; hastalis (also commonly – though mistakenly! – called “mako”); actual mako (Isurus sp.); megalodon; great white; nurse; cow; giant thresher; angustiden; auriculatus; and benedini.

The majority of shark teeth found in Florida date back to the Miocene and Pliocene epochs and are thus ~23 to ~2.58 million years old, with some rarer finds, especially in the northern part of the state, dating as far back as the Eocene (EE-oh-seen), some 50 mya.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

- The hows, whats, wheres, and whys of the Florida fossil scene: Fossil FAQ

- How Florida has changed over the last 30 million years: Florida’s Ancient Coastlines

- When North and South America collided: The Great American Biotic Interchange

- The Geologic Time Scale, Code Black style: An Absurdly Condensed Summary of the Earth’s Entire History

- Download/print/share: Free Edits

- One of the best shark-specific resources out there, authored by friend and fellow fossil enthusiast Logan Rash (@east_coast_fossils): My Shark Tooth Guide

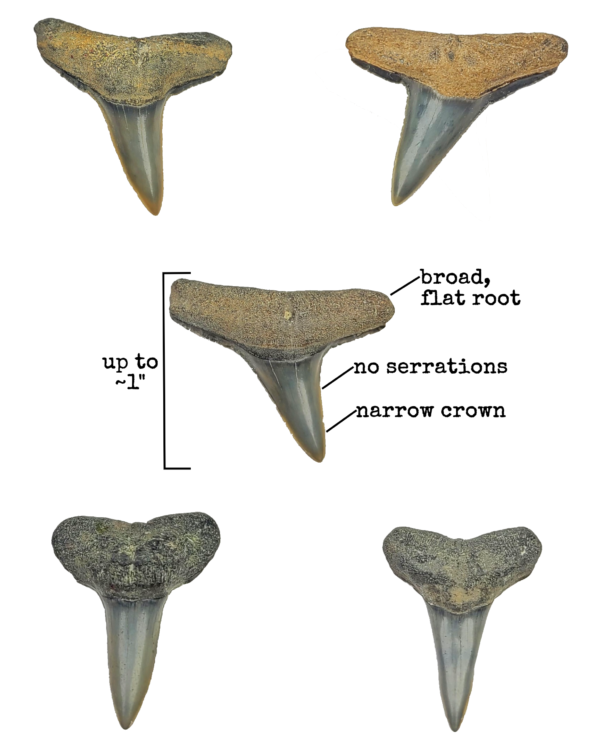

Lemon

(Negaprion brevirostris)

Modern lemon sharks primarily inhabit shallow, coastal waters of the eastern hemisphere. They’re thought to have evolved during the late Cretaceous period, some 75-95 mya (million years ago), meaning they co-existed with dinosaurs. Though relatively large (growing up to 11’ and 300+ lbs), they are a docile species and pose very little threat to humans. They’re named after the yellow hue of their skin, which offers excellent camouflage in their preferred shallow, sandy hunting grounds. Their teeth lack serrations, have narrow crowns with broad, flat roots, and resemble the letter “T”.

SHARK FACT

Sharks’ earliest direct ancestors (which took on all kinds of bizarre forms we’d hardly recognize as sharks today) date back to at least the Silurian period, ~440 mya (million years ago). Here’s a list of things “sharks” are older than: trees; amphibians; dinosaurs; reptiles; birds; Pangea; the Atlantic Ocean; the Rockies, Alps, Himalayas, and Andes; Saturn’s rings; and Polaris (the star itself, not just its run as the “North Star,” which is a super interesting astronomy tangent – Google “north star precession” to learn more!).

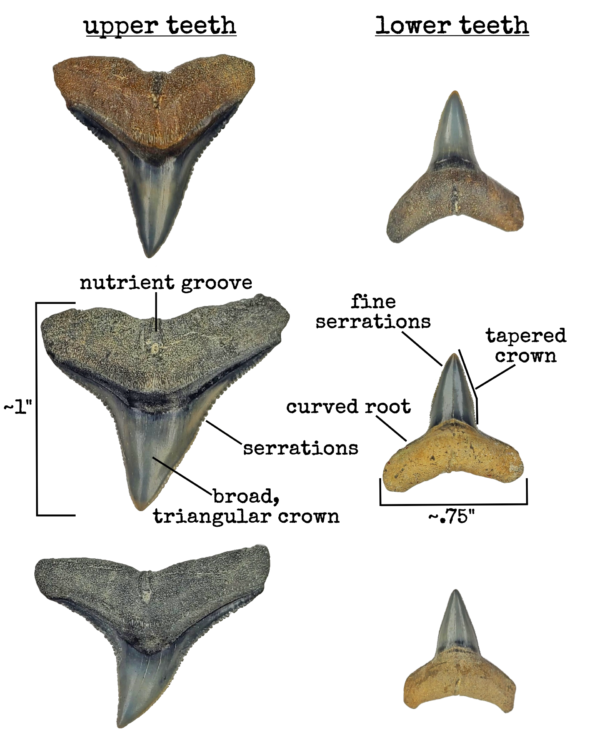

Bull

(Carcharhinus sp.)

Bull sharks are one of many species in the broad genus Carcharhinus, which also includes the dusky and silky. Teeth from within this genus often look very similar, making them difficult to tell apart. As such, they’re typically grouped together by collectors and simply referred to as “bulls.” Highly freshwater tolerant, bull sharks have been found in rivers over 1,000 miles upstream. Aggressive and unpredictable, they account for multiple attacks on humans every year, though luckily most aren’t fatal. Their upper teeth are broad and triangular with well-defined, tapering serrations (coarser near the root and finer at the tip), a plunging root, and a prominent nutrient groove while lowers, which are often confused with lemon shark teeth, are narrower, smaller, very finely serrated, taper inward about halfway down the crown, and have a curved root.

SHARK FACT

While the teeth of most other animals are firmly rooted directly into the jaw, shark teeth are held in place by special connective tissue in the “gums” and are lost continuously throughout a shark’s life. Most sharks have around 50 tooth positions, with 5-15 rows (or files) of teeth growing in each one. These rows operate like a conveyor belt: as one tooth is lost or damaged, a new one moves forward to take its place. Some sharks can go through 35,000 or more teeth in a lifetime. That’s part of the reason you find so many of them while fossil hunting!

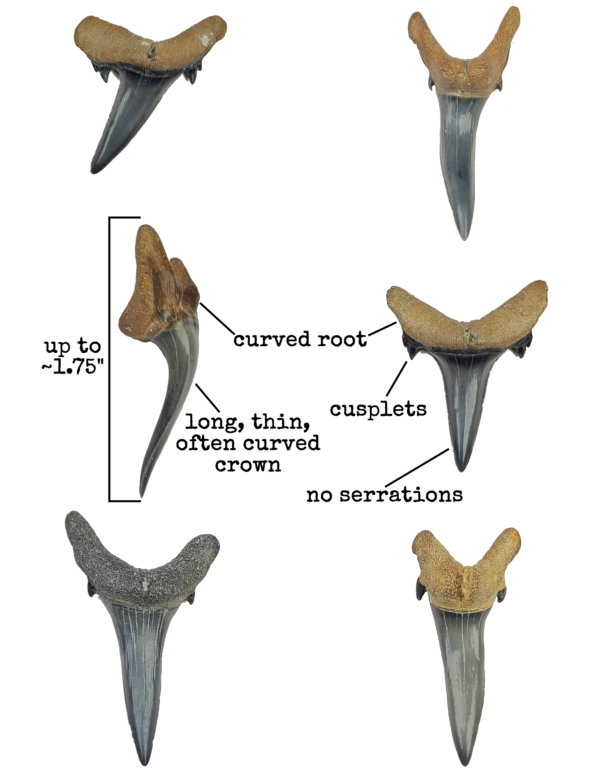

Sand Tiger

(Carcharias taurus)

Sand tiger sharks have been around for tens of millions of years. They inhabit temperate and sub-tropical coastal waters worldwide, with adults growing up to 11’ long and 350 lbs. Despite their fearsome appearance, they pose minimal threat to humans, instead using these long, needle-like teeth to grip their desired prey: slippery fish, smaller sharks, rays, and squid. Interestingly, they’re the only sharks known to “gulp” air at the surface. They store this air in their stomachs in order to achieve neutral buoyancy, which allows them to hover motionlessly just above the seafloor in wait of prey. A collectors’ favorite, sand tiger teeth are long and needle-like with tiny cusplets on either side of a markedly curved root.

SHARK FACT

You may have heard that if a shark stops moving it will no longer be able to breathe and eventually die. But is this actually true? For some sharks, like the great white and whale – yes! As obligate ram ventilators, the moment they stop moving, oxygen-rich water stops flowing through their gills. But many sharks, like the sand tiger, have special adaptations to combat this problem, such as buccal pumping, in which muscles in the cheeks are used to draw water in through the mouth and back out through the gills, ensuring a constant supply of oxygen-rich water to their motionless host.

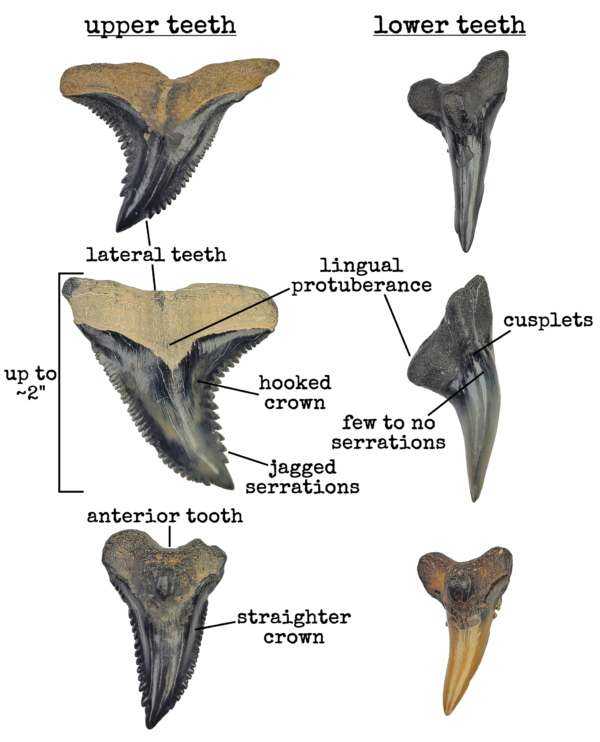

Hemipristis

(Hemipristis serra)

Hemipristis serra, aka the snaggletooth shark, is an extinct weasel shark that was widespread during the Miocene (~23 to ~5.3 mya, or million years ago). It was significantly larger than its 8’ long extant (still in existence) cousin, clocking in at 20’ in length. Upper and lower hemi teeth look quite different (and until recently were believed to be from two completely different species) and had opposing functions, with the broad, heavily serrated uppers acting as knives, cutting and tearing flesh, while the pointy, lightly or un-serrated lowers acted as forks, spearing prey and holding it in place. Note that upper lateral teeth (those toward the sides of the jaw) have a significant curve while upper anterior teeth (those toward the center of the jaw) are straighter and narrower. Lowers, which are often confused with sand tiger teeth, can be distinguished by the significant lingual protuberance, or hump, in the center of the root.

SHARK FACT

When an animal has upper and lower teeth that differ in size and shape it is said to have dignathic heterodonty (die-NATH-ick HET-err-oh-don-tee). Many sharks exhibit this trait (including several others listed here, such as bulls), but few as markedly as the Hemipristis.

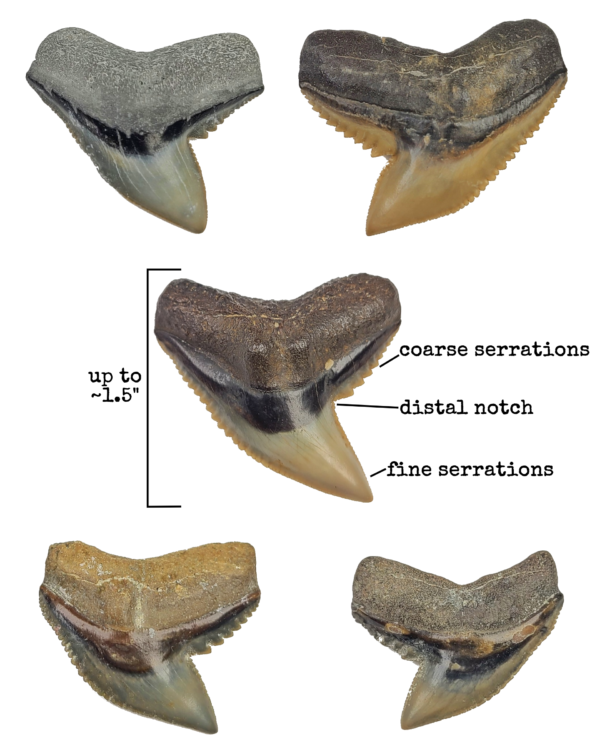

Tiger

(Galeocerdo cuvier)

Tiger sharks derive their name from the spots and stripes that dot their backsides, though these typically fade with age. Legendary for their diverse diets, common prey includes fish, birds, seals, dolphins, whales, crustaceans, squid, sea snakes, other sharks, and, notably, sea turtles. Edible items aren’t the only ones on the menu, however, as they’ve been found with everything from license plates to fur coats in their stomachs. Though their large size and dietary ambivalence make them dangerous to humans, attacks are still rare and fatalities even more-so. Among the most iconic shark teeth, they’re easily identified by their unique shape: a broad, plunging root and telltale notched, complexly serrated crown (their serrations have serrations of their own!)

SHARK FACT

The size and shape of each species’ teeth can tell you about their diet: long, needle-like teeth are ideal for spearing slippery fish and squid; large, triangular, serrated teeth for slicing through larger fish and especially marine mammals; and broad, flat teeth for crushing shelled and armored prey. Then there are non-functional vestigial teeth, as in the case of filter-feeders like basking, megamouth, and whale sharks, which are merely evolutionary remnants from earlier ancestors and no longer serve any practical use.

Tiger

(Galeocerdo mayumbensis)

Very little is known about this extinct species of tiger shark. It’s thought to have first appeared in the late Miocene (perhaps ~10 mya) and gone extinct shortly thereafter. Its teeth are very similar to G. cuvier, but with a taller, more rounded crown.

Tiger-like

(Physogaleus contortus)

Though once thought to be a species of tiger shark, this extinct group has since been reclassified to a totally new genus. Their teeth share obvious similarities with those of tiger sharks but are significantly smaller overall, with occasionally twisting crowns that are pointier, more slender, and have fewer serrations. Their shape indicates that they probably had a diet of slippery fish, rays, and squid, similar to sand tiger sharks.

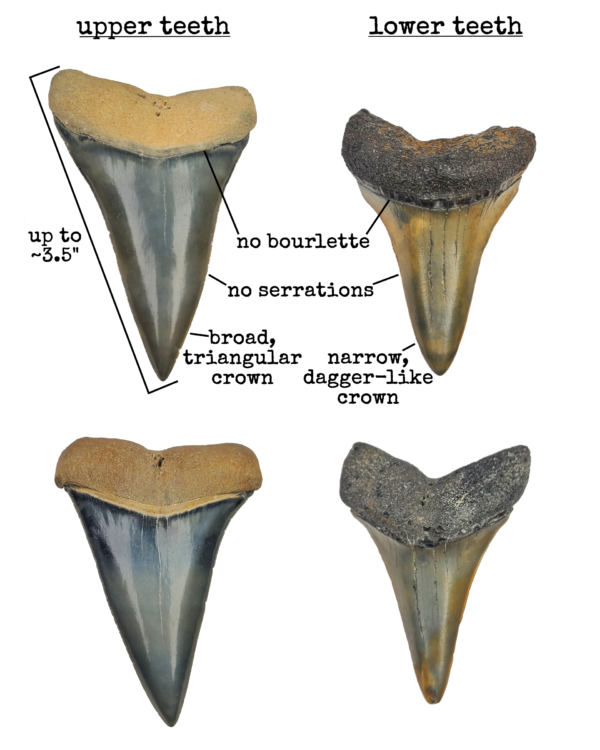

Hastalis

(Carcharodon hastalis)

The extinct hastalis, or lesser white, is among the most sought after shark teeth in Florida. While there has been a great deal of debate about the ancestral lineage of the hastalis throughout the years (you’ll often see them classified as either Isurus or Cosmopolitodus hastalis, or referred to by their still common nickname of “makos”), recent studies indicate that they’re actually ancestral to modern great whites. Indeed, the two species’ teeth share a great deal in common in terms of size and overall shape, with the hastalis simply lacking the serrations of their great white counterparts. Hastalis uppers are broad and triangular, while lowers are narrower with more sharply angled roots.

SHARK FACT

Sharks, along with their close cousins rays, skates, and sawfish (and distant cousins chimeras) comprise a class of fish called Chondrichthyes (kahn-DRIK-thee-eez): those with cartilaginous (car-tuh-LADGE-in-iss) skeletons rather than ones made of bone. Cartilage is both lighter and more flexible than bone, reducing a shark’s overall weight and allowing for quicker movements and improved agility underwater. However, without a bony rib cage to protect their internal organs, sharks can literally be crushed by their own weight out of the water.

Great White

(Carcharodon carcharias)

The great white is unquestionably the most [in]famous shark alive today. A sexually dimorphic species, females are larger than males, with the largest ever tagged (named Deep Blue) clocking in at 20′ and ~4,500 lbs (though the average female is ~16′ and the average male is ~13′). With a top speed of 35 mph, a diving capacity of nearly 4,000′, an estimated bite force of 4,000 psi, and a life span of 70+ years, the great white is among the most dominant apex predators in all of history. Their teeth tell this tale: a coarsely serrated crown seemingly custom built for slicing through flesh, with uppers being broad and triangular and lowers narrowing sharply from root to tip.

SHARK FACT

While great whites are often thought of as the “top dogs” of the sea, they do have one natural predator: Orcinus orca, the killer whale. Orcas have been observed ramming into great whites (and other large sharks) at high speeds, momentarily stunning them. They then flip the stunned shark over to induce tonic immobility, a reflex in sharks in which they become catatonic and effectively paralyzed, and hold them in that position until they drown. Their reward? Shark liver (which can comprise over 25% of a great white’s total body weight): a meal not only loaded with vital nutrients, but one that is more calorically dense than even whale blubber, and which is excised with almost surgical precision, as typically the rest of the now dead shark is left intact.

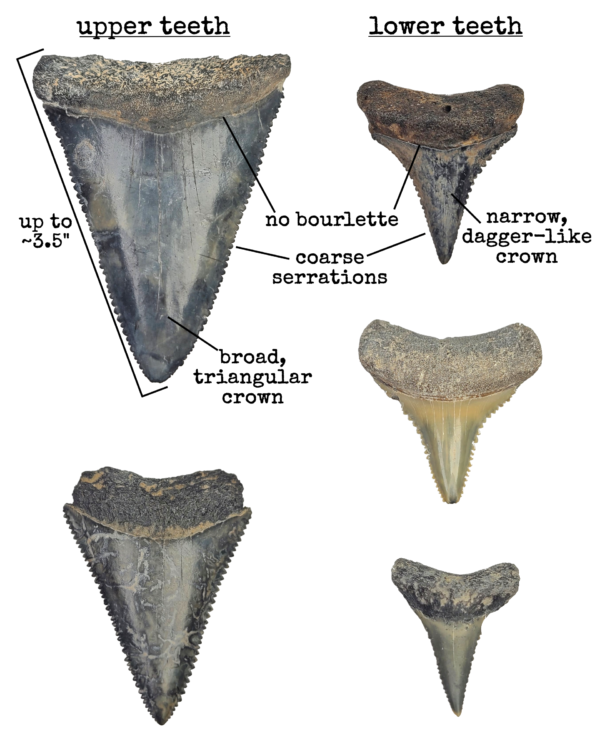

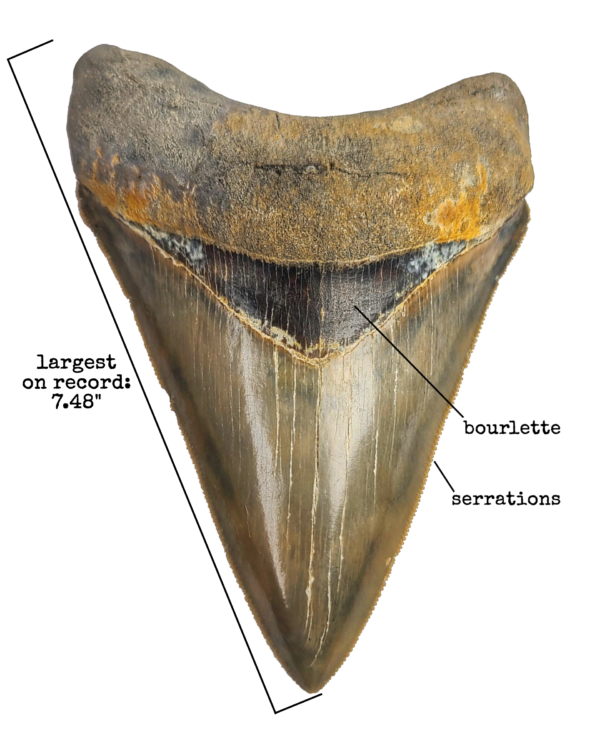

Megalodon

(Otodus megalodon)

The megalodon is the largest shark of all time. It terrorized seas worldwide from ~20 to ~3.6 million years ago, growing to an estimated 60+’ long and weighing 60+ tons. Its jaws maxed out at nearly 10’ wide and came equipped with up to 276 teeth (46 tooth positions with six sets growing in each row, or file) that could grow to over 7” long, with the largest tooth on record measuring 7.48” from tip to corner (which is how shark teeth are typically measured). Possessing the strongest bite force of any animal in history at an estimated 40,000 lbs/sq inch (which is 3 to 4 times higher than the estimated bite force of a T-Rex!), it feasted on large marine mammals such as dugongs, manatees, sea lions, seals, dolphins, and even whales, in addition to sea turtles, large fish, and other sharks.

It’s thought to have primarily hunted in warm, shallow seas across the globe, as evidenced by its fossilized teeth being found from Australia to Indonesia, Morocco, Peru, the entire southeastern coast of the US (from Florida to Maryland) and beyond (indeed, its teeth have been found on every continent except Antarctica). While scientists once believed that the megalodon was an ancestor of modern great whites, we now know that they evolved from completely different lineages and are not closely related at all.

Megalodon teeth are differentiated from those of other species by their sheer size and the fact that they possess both serrations and a bourlette (a triangular or V-shaped band between the root and crown) while lacking cusps. Uppers are broad and triangular; lowers are typically narrower, taper inward from root to tip, and have more sharply angled roots; and posteriors (those toward the very back of the jaw) have short, squat crowns with wide, thick roots.

(Want a megalodon of your own? Check out our megalodon tooth inventory and find the tooth of your dreams!)

SHARK FACT

The side most people think of as the “front” of a shark tooth is actually the back side! The labial, or outward facing side of shark teeth is actually relatively flat and featureless, whereas the lingual, or inward facing side is the one that gets all the attention (as evidenced by every tooth in this ID guide being featured from the lingual side

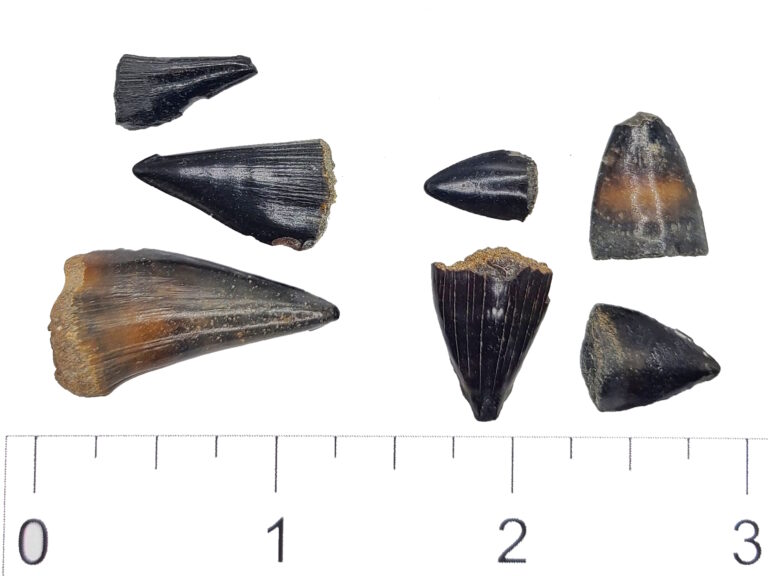

Barracuda teeth

Barracuda are large, aggressive, predatory marine (saltwater) fish often likened to piranhas of the sea. They typically have 100 or more teeth, with the largest specimens (they can grow up to 6 feet long) even surpassing 200. These teeth form in rows: one on the bottom jaw and two up top. The outer top row consists of small, saw-like teeth perfect for shredding flesh, while the much larger interior and lower “fangs” puncture and ensnare. These teeth come in two different shapes: triangular and symmetrical with a cutting edge on either side, or slightly curved and asymmetrical, with one cutting edge and one rounded. While barracuda have been known to harass divers and swimmers, they seldom attack. Lucky for us!

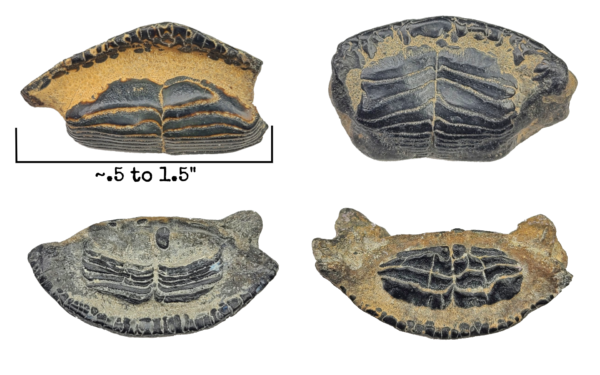

Burrfish mouth plates

Burr, puffer, and porcupinefish belong to the broader “blowfish” family (taxonomically, order). Many of the fish in this order possess sharp, spiny armor (hence the names “burr” and “porcupine”), some are highly venomous, and all have the ability to inflate when threatened by predators. Burr (featured here) and porcupinefish (which look similar but are typically larger, with up to 20+ layers of stacked enamel) have fused teeth, while pufferfish teeth are unfused (and significantly more rare). These “mouth plates” form a beak of sorts and are used to crush the fish’s armored prey. On the menu? Crabs, clams, sea snails, shrimp, urchins, barnacles, and more.

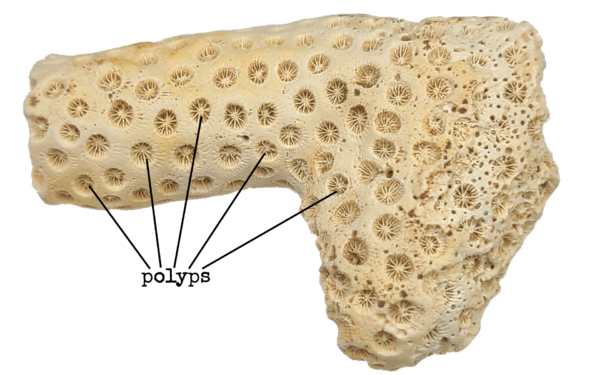

Coral

Despite their plant-like appearance, corals are actually animals, often forming colonies consisting of thousands of individual polyps – each one being a different animal! Finger coral, a species of stony coral, is one of the most abundant corals in the Caribbean and western Atlantic. They thrive in waters up to 65’ deep, so it’s no surprise they’re found so commonly – fossilized or otherwise – in Florida’s shallow seas.

Drum Fish teeth

Drum fish (which get their name from the drum-like croaking sounds adult males produce by vibrating a set of muscles against their swim bladders) possess what are called pharyngeal (fir-IN-jee-uhl), or throat, teeth. These molariform (moe-LAIR-ih-form), or molar-like, teeth are embedded in specialized throat plates, which act like a vice to crush the drum’s preferred armored prey of shellfish and crabs. Black drums in particular have one of the highest bite force to body weight ratios in all of nature, allowing them to make quick work of even the most robustly fortified shell.

Dugong rib

Dugongs, which are close relatives of manatees, once roamed Florida’s seas in huge numbers but are now found exclusively in the eastern hemisphere – the east coast of Africa, western India, southeast Asia, and northern Australia. Their ribs, which are extremely dense and therefore heavy, act as ballast (similar to a scuba diver’s weight belt), allowing them to achieve neutral buoyancy instead of merely bobbing around at the surface of the water. The more dense a bone is the more readily it will fossilize, and these certainly live up to the billing, being one of the most common fossil finds in the state. A general rule of thumb is that wherever dugong ribs are present, megalodon teeth are likely close by.

Gar scales

Gar are freshwater fish that can grow to 8’ long and weigh up to 300 lbs. They’ve existed for tens of millions of years, largely unchanged in that time. Their bony scales, also called ganoid scales, are unique in that they interlock rather than simply overlap, and are covered in both dentin (a component of teeth) and a crystalline mineral coating called ganoine. Another peculiar adaptation of gar is that they have the ability to “gulp” air from the surface into their swim bladders, which act as a rudimentary set of lungs, allowing them to live in stagnant, poorly oxygenated water other fish are unable to withstand.

Shark vertebrae (pl); vertebra (sg)

Vertebrae are the bones that make up the spinal column in vertebrates. Though shark skeletons are made of cartilage, their vertebral centra (central discs of the vertebrae) are more heavily mineralized than the rest of their skeletons and therefore occasionally fossilize.

Steinkerns

German for stone (stein) and kernel (kern), steinkerns (SHTINE-kerns) are the internal molds, or stone casings, of bivalves (hinge-shelled mollusks like clams or oysters) and gastropods (spiral-shelled mollusks like snails or whelks).

Stingray

Rays, together with their cousins sharks, skates, and sawfish (and distant cousins chimeras) comprise the class of fish called Chondrichthyes (kahn-DRIK-thee-eez): those with cartilaginous (car-tuh-LADGE-in-iss) skeletons rather than ones made of bone.

barbs

Their venomous, serrated tail barb is only used as a last line of defense, as rays would rather flee than fight. When deployed, it’s whipped to the side or over the stingray’s head like a scorpion. These stings are EXTREMELY painful and are why it’s best to heed the common Floridian refrain of doing the “stingray shuffle” when walking in the water. 😉

dermal denticles

Also known as placoid scales (and commonly called “mermaid nipples”), denticles are essentially modified teeth (not actual scales) that cover the skin of sharks, rays, and skates. They act not only as armor, offering protection from predators and parasites alike, but also increase the animal’s hydrodynamics by reducing drag and turbulence as it swims. If you’ve ever “pet” a ray, you’ll remember how smooth it felt when you went with the grain from head to tail but the second you went against the grain it felt like sandpaper. Those were the dermal denticles at work!

teeth

While true stingray (family Dasyatidae) teeth are tiny and often overlooked, eagle ray (family Myliobatidae; commonly just referred to as “stingray”) teeth are much larger and are common finds. These teeth grow in rows, fusing together to form broad, crushing “mouth plates” which are ideal for squashing the shells of their armored prey. These plates typically break apart into individual teeth after rays die, but on rare occasions can be found still fused together.

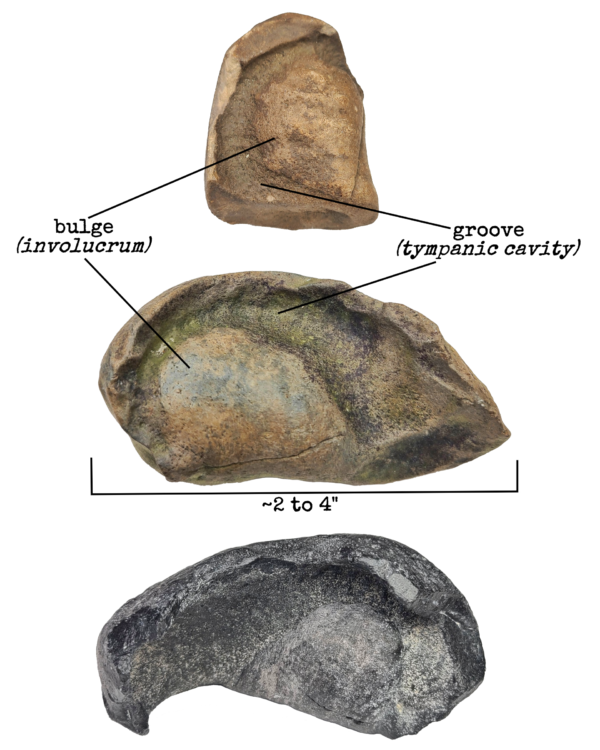

Whale tympanic bulla

(inner ear bone)

Cetaceans (seh-TAY-shenz) are a group of mammals that initially evolved on land before “re-entering” the water 50 some odd million years ago. Their immediate ancestors were amphibious and bred on land (similar to seals) and their closest modern relative is the hippopotamus. There are two modern groups of Cetaceans: the toothed whales, or Odontocetes (oh-DON-tuh-seats), which include sperm whales, orcas (killer whales), dolphins, and porpoises and which use high pitched clicks and pops to echolocate and communicate; and baleen whales, or Mysticetes (MISS-tuh-seats), which include blue, humpback, and right whales and which hear and communicate at much lower frequencies that can occasionally be heard by other whales up to an astonishing 1,000 miles away. As whales transitioned from amphibious creatures to purely aquatic ones, their ears had to adapt as well: from an early compromise of hearing just ok both above and below water, to the hyper-specialized, underwater eyes that they function as today. Few other animals are as reliant on hearing as whales.

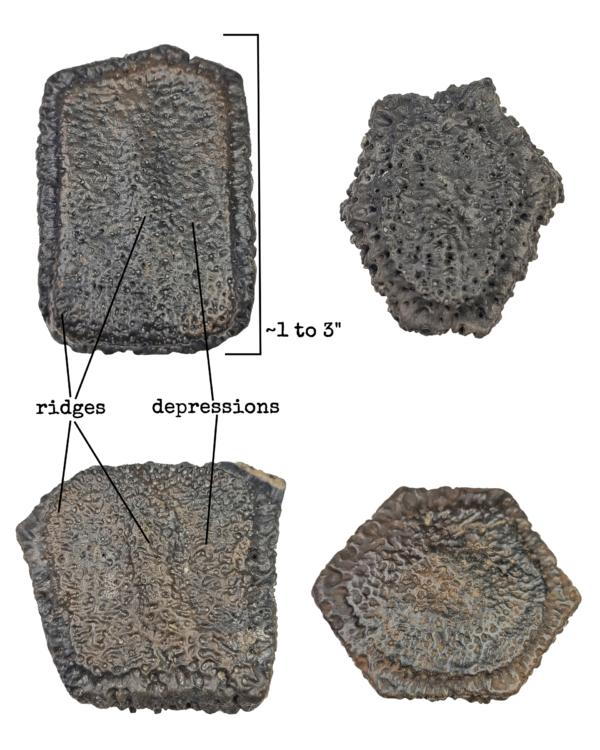

Alligator osteoderms

Latin for bone (osteo-) and skin (derm-), osteoderms are just that: bony deposits in the skin. In alligators and crocodiles, they serve three main functions: as armor; as a thermoregulatory apparatus (that is, they can either transfer warmth from the sun directly to the blood or dissipate heat if the animal becomes too warm); and to prevent acidosis, a condition in which acidic carbon dioxide builds up in the blood of a submerged, breath-holding animal, by releasing alkaline calcium and magnesium ions into the bloodstream, thereby neutralizing its pH level.

Alligator teeth

Mature alligators have 80 conical teeth, which they lose and replace by the thousands over the course of their lives. Replacements grow in from below the existing tooth at about the same rate as human fingernails. A rootless, hollow bottomed tooth was lost by a living animal, whereas a rooted tooth came from a deceased one. The largest (modern) American alligator on record was captured in 2014 and was nearly 16’ and weighed over 1000 lbs.

South Florida is the only place in the world where alligators and crocodiles coexist. Both species are ancient, dating back at least tens of millions of years, but they weren’t always the only players on the scene. During the Miocene, Florida was also home to another crocodile called Thecachampsa americana. This now extinct crocodilian is thought to have grown to over 20’ long, possessing an elongated but incredibly thin, gharial-like snout. Though each species existed in its own particular ecological niche, there was no doubt some overlap in habitats, perhaps even leading to confrontations in a battle for ultimate crocodilian supremacy.

Giant Armadillo scutes

Though commonly called giant armadillos, these animals were actually pampatheres, an extinct line of armadillo-like creatures. Originally evolving in South America, they dispersed northward after the Isthmus of Panama was formed roughly 2.7 mya in an event known as the Great American Biotic Interchange, in which tremendous migrations of animal species took place between the Americas via this newly formed land bridge. Unlike modern armadillos, which are insectivorous (insect eaters) or omnivorous (eating a mixed diet of plants and animals), giant armadillos were strictly herbivorous (plant eaters). They were much larger than the giant armadillos of today (found in South America), with the larger of the two species (septentrionalis) growing to 3’ tall, 6.5’ long, and weighing 600 lbs. Their shells were covered by hundreds of individual scutes (also called osteoderms), or bony, scale-like structures in the skin, of many shapes, sizes, and functions, with some even overlapping one another (called imbricating scutes), forming bands similar to those of modern armadillos. These bands afforded flexibility while still offering protection from predators.

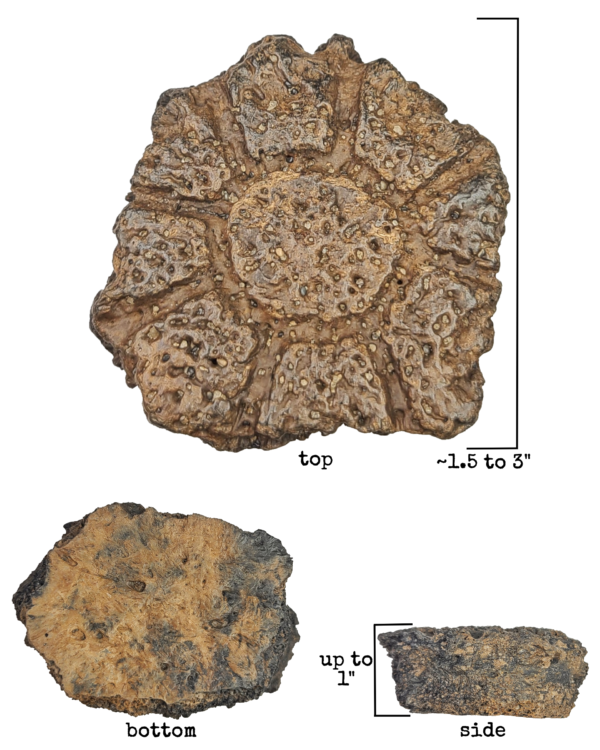

Glyptodont scutes

Glyptodonts are an extinct relative of armadillos, anteaters, and sloths (together forming the clade – a grouping of animals that all evolved from a common ancestor – Xenarthra (zen-ARTH-ruh), latin for “strange joints”) that initially evolved in South America before migrating northward after the Isthmus of Panama was formed some 2.7 mya. They dwarfed their giant armadillo cousins, growing to 5’ tall, 11’ long, and weighing over 4,000 lbs: about the size (and roughly the shape) of a Volkswagen Beetle. Their heavily armored heads, tails, and dome-shaped shells were equipped with over a thousand individual scutes (also called osteoderms), or bony, scale-like structures in the skin, and they bore a slight resemblance to the unrelated and much older – but similarly armored – Ankylosaurid dinosaurs in a case of what paleontologists call convergent evolution, in which ecological pressures lead two or more different species to evolve similar traits, features, or characteristics.

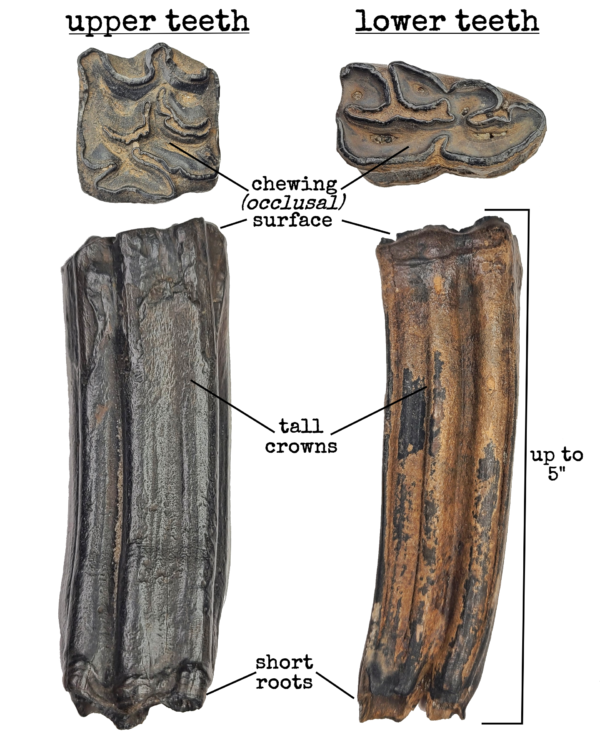

Horse teeth

The evolutionary lineage of horses is perhaps the best attested in all of paleontology, starting in North America 50+ mya with a 20” tall hoofed mammal called Eohippus. Unlike modern horses, which are grazers (grass-eaters) and have one, unpadded, hoof per leg, this diminutive ancestor was a browser (meaning it ate leaves, soft shoots, and/or shrubs) and had four padded hooves per front leg with three in the rear. Over the course of horse evolution, which is a complex web that illustrates how diverse evolutionary mechanisms can truly be, the following trends ultimately won out: increase in overall size; reduction in number of hooves and loss of footpads; lengthening of legs and a fusion of the lower leg bones; increase in head and brain size; and a transition to crested, high-crowned teeth ideal for grazing (called hypsodont dentition).

When a horse eats, it inadvertently yanks up grit and soil in addition to grass. Grass requires a lot of hard, grinding chewing to make it digestible and is itself full of microscopic, abrasive silica granules called phytoliths. The chewing of this exogenous (originating from outside an organism) grit in addition to the abrasive phytoliths naturally present in grass causes horse teeth to literally erode away over time. As a result, their teeth evolved to slowly erupt out of the gum line as they’re worn down. Each tooth tells a story: a long tooth (adult molars start at ~5”) indicates that the horse it belonged to died at a young age, while a severely worn tooth, sometimes hardly more than just the roots, relays that its owner lived a long life before ultimately succumbing to starvation or, no longer able to eat and in a weakened state, predation.

Ivory

Ivory is a form of dentin (a component of teeth) that is found in the tusks of certain mammals, most notably elephants. There are several now extinct elephant relatives that once called Florida home, with the most widespread being the Columbian mammoth (which had long, curved tusks that grew to 16’ long), American mastodon (whose tusks were typically slightly shorter and considerably straighter), and various species of gomphothere (including the bizarre, shovel tusked Amebelodon). Look for cross-hatched patterns (called Schreger lines), as they’re a dead giveaway of ivory.

Mastodon tooth fragments

Though similar in height to modern elephants (growing to ~10’ tall), mastodons were built much more robustly: they had shorter legs but wider, stockier bodies, making them nearly twice as heavy as a similarly sized elephant. Mastodons were browsers (meaning they ate shrubs, twigs, and leaves rather than grasses), something we’re able to glean from their dentition, or the shape, structure, and arrangement of their teeth, which in their case consisted of a series of cone-like cusps, or lophs, a dentition shared with their even more bizarre, occasionally shovel-tusked relatives the gomphotheres.

Misc tooth/enamel fragments

Not every tooth you find is complete. In fact, the vast majority of specimens are broken! Common tooth fragments include horse (pictured here at the top), mammoth, mastodon, deer, tapir (bottom left), llama, camel, peccary, beaver, capybara (bottom right), bison, ground sloth, alligator, giant armadillo, glyptodont, raccoon, rodent, and others. From browsers to grazers, carnivores to herbivores, and everything in between.

Tortoise leg spurs

Giant tortoises grew to 5-6’ in length and weighed up to 600 lbs, equal to or larger than the modern Galapagos tortoise. Their legs were covered in bony growths called osteoderms, or spurs, which are thought to have been used for combat, mating, digging, and/or defense. Though we’re unsure how long these giant tortoises lived, their modern cousins are some of the longest-living animals on the planet, often surpassing 200 years of age.

Turtle/Tortoise shell

A turtle’s shell comprises the upper shell, or carapace (KARE-uh-pis) and the bottom shell, or plastron (PLA-strun). Though these shell fragments are some of the most common fossil finds in the state, their often mesmerizing patterns make them a favorite with collectors.

Turtle neural elements

Turtle neural elements are one of the most easily identified parts of a turtle’s upper shell. They form the central ridge of the carapace and fuse to the spinal column. These are always a special find.

Calcite crystals

While calcite (CaCO₃; KAL-site) is one of the most common minerals in Florida, it’s rarely found in crystal form, as conditions leading to its formation have to be just right and it is highly susceptible to even the weakest acids. Here, calcite in groundwater seeped into the empty spaces in and around fossilized clams, sea snails, and coral and eventually crystallized, in a process similar to how geodes form.

Misc bone

Miscellaneous bits and pieces of fossilized bone.

Misc modern teeth

Not everything you find is fossilized, of course! Possible species here include pig, cow, raccoon, opossum, squirrel, alligator, deer, horse, etc.